I've recently looked into DSPy, a cutting-edge framework developed by the Stanford NLP group aimed at algorithmically optimizing language model (LM) prompts. Over the last three days, I've gathered some initial impressions and valuable insights into DSPy. Note that my observations are not meant to replace the official documentation of DSPy. In fact, I highly recommend reading through their documentation and README at least once before diving into this post. My discussion here reflects a preliminary understanding of DSPy, having spent a few days exploring its capabilities. There are several advanced features, such as DSPy Assertions, Typed Predictor, and LM weights tuning, that I have yet to explore thoroughly.

Despite my background with Jina AI, which primarily focuses on the search foundation, my interest in DSPy was not directly driven by its potential in Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG). Instead, I was intrigued by the possibility of leveraging DSPy for automatic prompt tuning to address some generation tasks.

If you're new to DSPy and seeking an accessible entry point, or if you're familiar with the framework but find the official documentation to be confusing or overwhelming, this article is intended for you. I also opt not to adhere strictly to DSPy's idiom, which may seem daunting to newcomers. That said, let's dive deeper.

tagWhat I Like About DSPy

tagDSPy Closing the Loop of Prompt Engineering

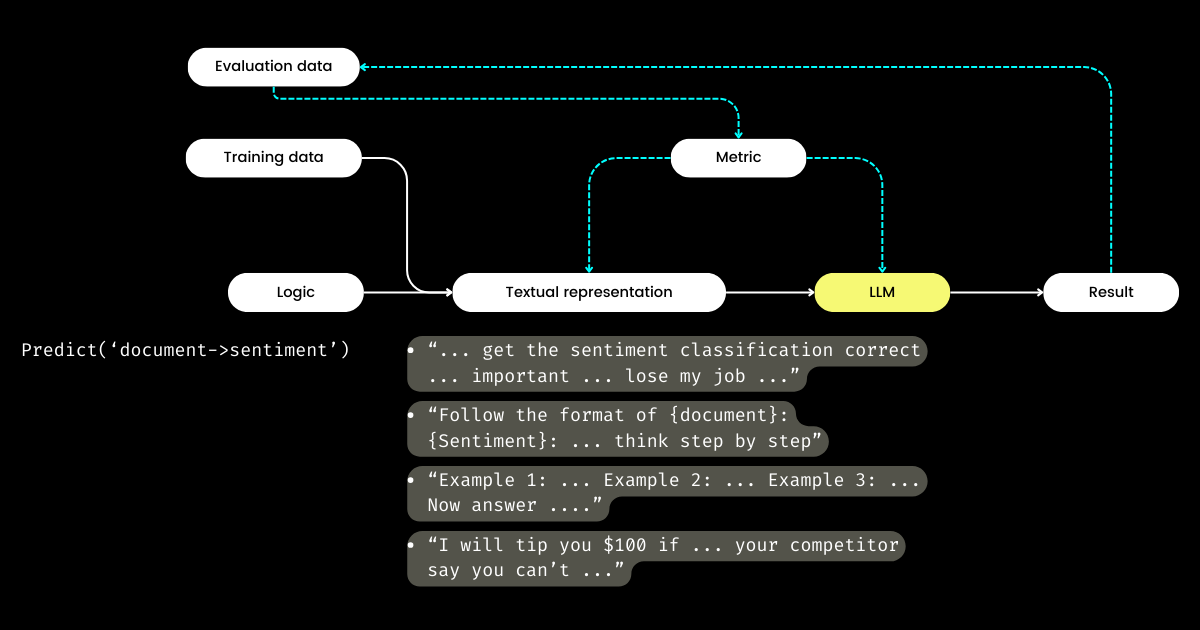

What excites me most about DSPy is its approach to closing the loop of the prompt engineering cycle, transforming what is often a manual, handcrafted process into a structured, well-defined machine learning workflow: i.e. preparing datasets, defining the model, training, evaluating, and testing. In my opinion, this is the most revolutionary aspect of DSPy.

Traveling in the Bay Area and talking to a lot of startup founders focused on LLM evaluation, I've encountered frequent discussions about metrics, hallucinations, observability, and compliance. However, these conversations often don't progress to the critical next steps: With all these metrics in hand, what do we do next? Can tweaking the phrasing in our prompts, in hopes that certain magic words (e.g., "my grandma is dying") might boost our metrics, be considered a strategic approach? This question has remained unanswered by many LLM evaluation startups, and it was one I couldn't tackle either—until I discovered DSPy. DSPy introduces a clear, programmatic method for optimizing prompts based on specific metrics, or even for optimizing the entire LLM pipeline, including both prompts and LLM weights.

Harrison, the CEO of LangChain, and Logan, the former OpenAI Head of Developer Relations, have both stated on the Unsupervised Learning Podcast that 2024 is expected to be a pivotal year for LLM evaluation. It is for this reason that I believe DSPy deserves more attention than it is right now, as DSPy provides the crucial missing piece of the puzzle.

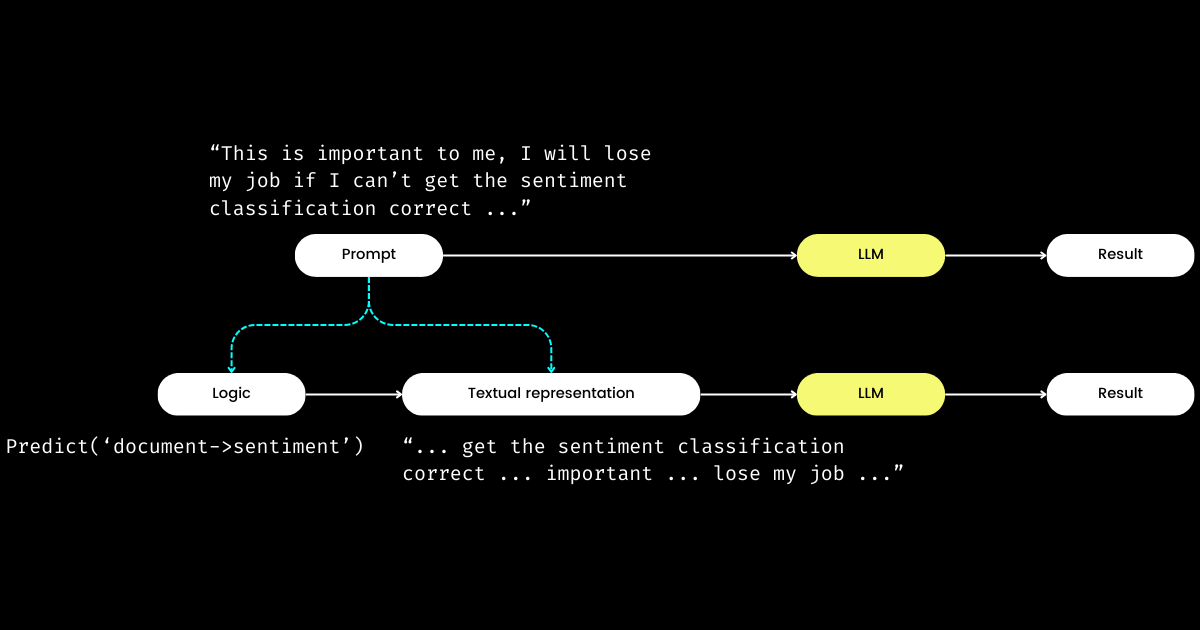

tagDSPy Separating Logic From Textual Representation

Another aspect of DSPy that impresses me is that, it formulates prompt engineering into a reproducible and LLM-agnostic module. To achieve that, it pulls the logic from the prompt, creating a clear separation of concerns between the logic and the textual representation, as illustrated below.

dspy.Module,) and its textual representation. Logic is immutable, reproducible, testable and LLM-agnostic. Textual representation is just the consequence of the logic.DSPy's concept of logic as the immutable, testable, and LLM-agnostic "cause", with textual representation merely as its "consequence", may initially seem perplexing. This is especially true in light of the widespread belief, that "the future of programming language is natural language." Embracing the idea that "prompt engineering is the future," one might experience a moment of confusion upon encountering DSPy's design philosophy. Contrary to the expectation of simplification, DSPy introduces an array of modules and signature syntaxes, seemingly regressing natural language prompting to the complexity of C programming!

But why take this approach? My understanding is that at the heart of prompt programming lies the core logic, with communication serving as an amplifier, potentially enhancing or diminishing its effectiveness. The directive "Do sentiment classification" represents the core logic, whereas phrase like "Follow these demonstrations or I will fire you" is one way to communicate it. Analogous to real-life interactions, difficulties in getting things done often stem not from flawed logic but from problematic communications. This explains why many, particularly non-native speakers, find prompt engineering challenging. I've observed highly competent software engineers in my company struggle with prompt engineering, not due to a lack of logics, but because they do not "speak the vibe." By separating the logic from the prompt, DSPy enables deterministic programming of logic via dspy.Module, allowing developers to shift focus to logic in the same way they would in traditional engineering, irrespective of the LLM used.

So, if developers focus on the logic who then manages the textual representation? DSPy takes on this role, utilizing your data and evaluation metrics to refine the textual representation—everything from determining the narrative focus to optimizing hints, and choosing good demonstrations. Remarkably, DSPy can even use evaluation metrics to fine-tune the LLM weights!

To me, DSPy's key contributions—closing the loop of training and evaluation in prompt engineering and separating logic from textual representation—underscore its potential significance to LLM/Agent systems. Ambitious vision for sure, but definitely necessary!

tagWhat I Think DSPy Can Improve

First, DSPy presents a steep learning curve for newcomers due to its idioms. Terms like signature, module, program, teleprompter, optimization, and compile can be overwhelming. Even for those proficient in prompt engineering, navigating these concepts within DSPy can be a challenging maze.

This complexity echoes my experience with Jina 1.0, where we introduced a slew of idioms such as chunk, document, driver, executor, pea, pod, querylang and flow (we even designed adorable stickers to help user remember!).

Most of these early concepts were removed in later Jina refactoring. Today, only Executor, Document, and Flow have survived from "the great purge." We did add a new concept, Deployment, in Jina 3.0; so that evens things out. 🤷

This problem isn't unique to DSPy or Jina; recall the myriad concepts and abstractions introduced by TensorFlow between versions 0.x to 1.x. I believe this problem often emerges in the early stages of software frameworks, where there's a push to reflect academic notations directly in the codebase to ensure maximum accuracy and reproducibility. However, not all users value such granular abstractions, with preferences varying from the desire for simple one-liners to demands for greater flexibility. I discussed this topic of abstraction in software frameworks extensively in a 2020 blog post, which interested readers might find worthwhile.

Second, the documentation of DSPy sometimes falls short in terms of consistency. Terms like module and program, teleprompter and optimizer, or optimize and compile (sometimes referred to as training or bootstrapping) are used interchangeably, adding to the confusion. Consequently, I spent my initial hours with DSPy trying to decipher exactly what it optimizes and what the process of bootstrapping entails.

Despite these hurdles, as you delve deeper into DSPy and revisit the documentation, you'll likely experience moments of clarity where everything starts to click, revealing the connections between its unique terminology and the familiar constructs seen in frameworks like PyTorch. However, DSPy undoubtedly has room for improvement in future versions, particularly in making the framework more accessible to prompt engineers without a background in PyTorch.

tagCommon Stumbling Blocks for DSPy Newbies

In the sections below, I've compiled a list of questions that initially stymied my progress with DSPy. My aim is to share these insights in the hope that they might clarify similar challenges for other learners.

tagWhat are teleprompter, optimization, and compile? What's exactly being optimized in DSPy?

In DSPy, "Teleprompters" is the optimizer, (and looks like @lateinteraction is revamping the docs and code to clarify this). The compile function acts at the heart of this optimizer, akin to calling optimizer.optimize(). Think of it as the DSPy equivalent of training. This compile() process aims to tune:

- the few-shot demonstrations,

- the instructions,

- the LLM's weights

However, most beginner DSPy tutorials won't delve into weights and instruction tuning, leading to the next question.

tagWhat's bootstrap in DSPy all about?

Bootstrap refers to the creation of self-generated demonstrations for few-shot in-context learning, a crucial part of the compile() process (i.e., optimization/training as I mentioned above). These few-shot demos are generated from user-given labeled data; and one demo often consists of input, output, rationale (e.g., in Chains of Thought), and intermediate inputs & outputs (for multi-stage prompts). Of course, quality few-shot demos are key to the output excellence. To that, DSPy allows user-defined metric functions to ensure only demos that meet certain criteria are chosen, leading to the next question.

tagWhat's DSPy metric function?

After hands-on experience with DSPy, I've come to believe that the metric function needs far more emphasis than what the current documentation provides. The metric function in DSPy plays a crucial role in both evaluation and training phases, acting as a "loss" function as well, thanks to its implicit nature (controlled by trace=None):

def keywords_match_jaccard_metric(example, pred, trace=None):

# Jaccard similarity between example keywords and predicted keywords

A = set(normalize_text(example.keywords).split())

B = set(normalize_text(pred.keywords).split())

j = len(A & B) / len(A | B)

if trace is not None:

# act as a "loss" function

return j

return j > 0.8 # act as evaluationThis approach differs significantly from traditional machine learning, where the loss function is usually continuous and differentiable (e.g., hinge/MSE), while the evaluation metric might be entirely different and discrete (e.g., NDCG). In DSPy, the evaluation and loss functions are unified in the metric function, which can be discrete and most often returns a boolean value. The metric function can also integrate an LLM! In the example below, I implemented a fuzzy match using LLM to determine if the predicted value and the gold standard answer are similar in magnitude, e.g., "1 million dollars" and "$1M" would return true.

class Assess(dspy.Signature):

"""Assess the if the prediction is in the same magnitude to the gold answer."""

gold_answer = dspy.InputField(desc='number, could be in natural language')

prediction = dspy.InputField(desc='number, could be in natural language')

assessment = dspy.OutputField(desc='yes or no, focus on the number magnitude, not the unit or exact value or wording')

def same_magnitude_correct(example, pred, trace=None):

return dspy.Predict(Assess)(gold_answer=example.answer, prediction=pred.answer).assessment.lower() == 'yes'As powerful as it is, the metric function significantly influences the DSPy user experience, determining not only the final quality assessment but also affecting the optimization results. A well-designed metric function can lead to optimized prompts, whereas a poorly crafted one can cause the optimization to fail. When tackling a new problem with DSPy, you may find yourself spending as much time designing the logic (i.e., DSPy.Module) as you do on the metric function. This dual focus on logic and metrics can be daunting for newcomers.

tag"Bootstrapped 0 full traces after 20 examples in round 0" what does this mean?

This message emits quietly during compile() deserves your highest attention, as it essentially means that optimization/compilation failed, and the prompt you get is no better than simple few-shot. What goes wrong? I've summarized some tips to help you debug ur DSPy program when encounter such message:

Your Metric Function is Incorrect

Is the function your_metric, used in BootstrapFewShot(metric=your_metric), correctly implemented? Conduct some unit tests. Does your_metric ever return True, or does it always return False ? Note that returning True is crucial because it's the criterion for DSPy to consider the bootstrapped example a "success." If you return every evaluation as True, then every example is considered a "success" in bootstrapping! This isn't ideal, of course, but it's how you can adjust the strictness of the metric function to change the "Bootstrapped 0 full traces" result. Note that although DSPy documents that metrics can return scalar values as well, after looking at the underlying code, I wouldn't recommend it for newbies.

Your Logic (DSPy.Module) is Incorrect

If the metric function is correct, then you need to check if your logic dspy.Module is correctly implemented. First, verify that the DSPy signature is correctly assigned for each step. Inline signatures, such as dspy.Predict('question->answer'), are easy to use, but for quality's sake, I strongly suggest implementing with class-based signatures. Specifically, add some descriptive docstrings to the class, fill in desc fields for InputField and OutputField—these all provide the LM with hints about each field. Below I implemented two multi-stage DSPy.Module for solving Fermi problems, one with in-line signature, one with class-based signature.

class FermiSolver(dspy.Module):

def __init__(self):

super().__init__()

self.step1 = dspy.Predict('question -> initial_guess')

self.step2 = dspy.Predict('question, initial_guess -> calculated_estimation')

self.step3 = dspy.Predict('question, initial_guess, calculated_estimation -> variables_and_formulae')

self.step4 = dspy.ReAct('question, initial_guess, calculated_estimation, variables_and_formulae -> gathering_data')

self.step5 = dspy.Predict('question, initial_guess, calculated_estimation, variables_and_formulae, gathering_data -> answer')

def forward(self, q):

step1 = self.step1(question=q)

step2 = self.step2(question=q, initial_guess=step1.initial_guess)

step3 = self.step3(question=q, initial_guess=step1.initial_guess, calculated_estimation=step2.calculated_estimation)

step4 = self.step4(question=q, initial_guess=step1.initial_guess, calculated_estimation=step2.calculated_estimation, variables_and_formulae=step3.variables_and_formulae)

step5 = self.step5(question=q, initial_guess=step1.initial_guess, calculated_estimation=step2.calculated_estimation, variables_and_formulae=step3.variables_and_formulae, gathering_data=step4.gathering_data)

return step5Fermi problem solver using in-line signature only

class FermiStep1(dspy.Signature):

question = dspy.InputField(desc='Fermi problems involve the use of estimation and reasoning')

initial_guess = dspy.OutputField(desc='Have a guess – don’t do any calculations yet')

class FermiStep2(FermiStep1):

initial_guess = dspy.InputField(desc='Have a guess – don’t do any calculations yet')

calculated_estimation = dspy.OutputField(desc='List the information you’ll need to solve the problem and make some estimations of the values')

class FermiStep3(FermiStep2):

calculated_estimation = dspy.InputField(desc='List the information you’ll need to solve the problem and make some estimations of the values')

variables_and_formulae = dspy.OutputField(desc='Write a formula or procedure to solve your problem')

class FermiStep4(FermiStep3):

variables_and_formulae = dspy.InputField(desc='Write a formula or procedure to solve your problem')

gathering_data = dspy.OutputField(desc='Research, measure, collect data and use your formula. Find the smallest and greatest values possible')

class FermiStep5(FermiStep4):

gathering_data = dspy.InputField(desc='Research, measure, collect data and use your formula. Find the smallest and greatest values possible')

answer = dspy.OutputField(desc='the final answer, must be a numerical value')

class FermiSolver2(dspy.Module):

def __init__(self):

super().__init__()

self.step1 = dspy.Predict(FermiStep1)

self.step2 = dspy.Predict(FermiStep2)

self.step3 = dspy.Predict(FermiStep3)

self.step4 = dspy.Predict(FermiStep4)

self.step5 = dspy.Predict(FermiStep5)

def forward(self, q):

step1 = self.step1(question=q)

step2 = self.step2(question=q, initial_guess=step1.initial_guess)

step3 = self.step3(question=q, initial_guess=step1.initial_guess, calculated_estimation=step2.calculated_estimation)

step4 = self.step4(question=q, initial_guess=step1.initial_guess, calculated_estimation=step2.calculated_estimation, variables_and_formulae=step3.variables_and_formulae)

step5 = self.step5(question=q, initial_guess=step1.initial_guess, calculated_estimation=step2.calculated_estimation, variables_and_formulae=step3.variables_and_formulae, gathering_data=step4.gathering_data)

return step5Fermi problem solver using class-based signature with more comprehensive description on each field.

Also, check the def forward(self, ) part. For multi-stage Modules, ensure the output (or all outputs like the in FermiSolver) from the last step is fed as input to the next step.

Your Problem is Just Too Hard

If both the metric and module seem correct, then it's possible your problem is just too challenging and the logic you implemented is not enough for solving it. Therefore, DSPy finds it is infeasible to bootstrap any demo given your logic and metric function. At this point, here are some options you can consider:

- Use a more powerful LM. For example, replacing

gpt-35-turbo-instructwithgpt-4-turboas the student's LM, use a stronger LM as the teacher. This can be often quite effective. After all, a stronger model means better comprehension on the prompts. - Improve your logic. Add or replace some steps in your

dspy.Modulewith more complicated ones. e.g., replacePredicttoChainOfThoughtProgramOfThought, addingRetrievalstep. - Add more training examples. If 20 examples is not enough, aim for 100! You can then hope one example passes the metric check and is picked by

BootstrapFewShot. - Reformulate the problem. Often, a problem becomes unsolvable when the formulation is incorrect. But if you change an angle to look at it, things could be much easier and more obvious.

In practice, the process involves a blend of trial and error. For instance, I tackled a particularly challenging problem: generating an SVG icon similar to Google Material Design icons based on two or three keywords. My initial strategy was to utilize a simple DSPy.Module that uses dspy.ChainOfThought('keywords -> svg'), paired with a metric function that assessed visual similarity between the generated SVG and the ground truth Material Design SVG, similar to a pHash algorithm. I began with 20 training examples, but after the first round, I ended up with "Bootstrapped 0 full traces after 20 examples in round 0", indicating that the optimization had failed. By increasing the dataset to 100 examples, revising my module to incorporate multiple stages, and adjusting the threshold of the metric function, I eventually achieved 2 bootstrapped demonstrations and managed to obtain some optimized prompts.