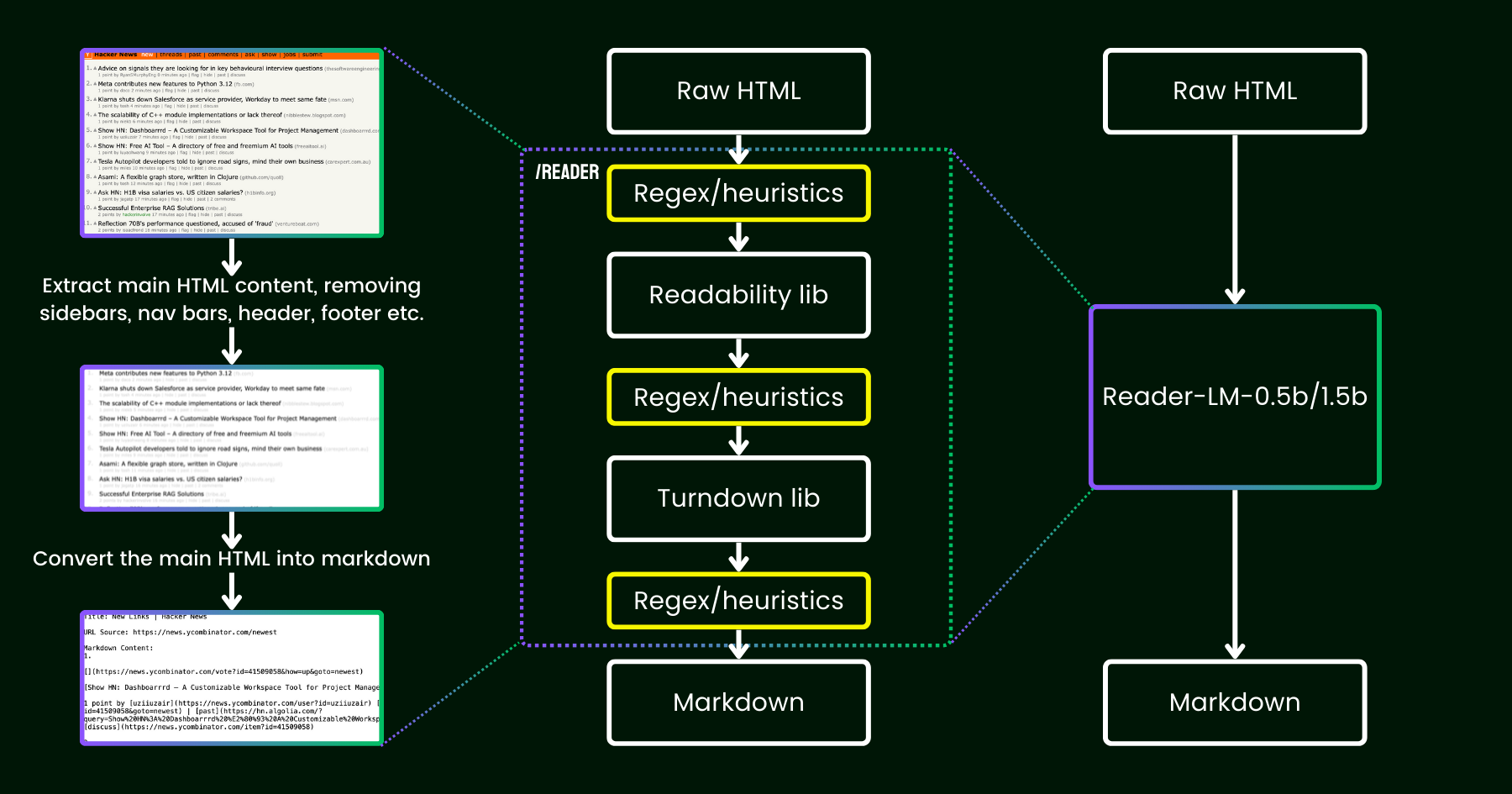

In April 2024, we released Jina Reader, a simple API that converts any URL into LLM-friendly markdown with just a simple prefix: r.jina.ai. Despite the sophisticated network programming behind the scenes, the core "reading" part is quite straightforward. First, we use a headless Chrome browser to fetch the source of the webpage. Then, we leverage Mozilla’s Readability package to extract the main content, removing elements like headers, footers, navigation bars, and sidebars. Finally, we convert the cleaned-up HTML into markdown using regex and the Turndown library. The result is a well-structured markdown file, ready to be used by LLMs for grounding, summarizing, and reasoning.

In the first few weeks after the release of Jina Reader, we received a lot of feedback, particularly regarding the quality of the content. Some users found it too detailed, while others felt it wasn’t detailed enough. There were also reports that the Readability filter removed the wrong content or that Turndown struggled to convert certain parts of the HTML into markdown. Fortunately, many of these issues were successfully resolved by patching the existing pipeline with new regex patterns or heuristics.

Since then, we’ve been pondering one question: instead of patching it with more heuristics and regex (which becomes increasingly difficult to maintain and isn’t multilingual friendly), can we solve this problem end-to-end with a language model?

reader-lm, replacing the pipeline of readability+turndown+regex heuristics using a small language model.At first glance, using LLMs for data cleaning might seem excessive due to their low cost-efficiency and slower speeds. But what if we're considering a small language model (SLM) — one with fewer than 1 billion parameters that can run efficiently on the edge? That sounds much more appealing, right? But is this truly feasible or just wishful thinking? According to the scaling law, fewer parameters generally lead to reduced reasoning and summarizing capabilities. So an SLM might even struggle to generate any meaningful content if its parameter size is too small. To explore this further, let’s take a closer look at the HTML-to-Markdown task:

- First, the task we’re considering isn’t as creative or complex as typical LLM tasks. In the case of converting HTML to markdown, the model primarily needs to selective-copy from the input to the output (i.e., skipping over HTML markup, sidebars, headers, footers), with minimal effort spent on generating new content (mostly inserting markdown syntax). This contrasts sharply with the broader tasks LLMs handle, such as generating poems or writing code, where the output involves much more creativity and is not a direct copy-paste from the input. This observation suggests that an SLM might work, as the task seems simpler than more general text generation.

- Second, we need to prioritize the long-context support. Modern HTML often contains much more noise than simple

<div>markup. Inline CSS and scripts can easily balloon the code to hundreds of thousands of tokens. For an SLM to be practical in this scenario, the context length must be sufficiently large. Token-length like 8K or 16K is not useful at all.

It seems that what we need is a shallow-but-wide SLM. "Shallow" in the sense that the task is primarily simple "copy-paste", hence fewer transformer blocks are needed; and "wide" in the sense that it requires long context support to be practical so attention mechanism needs some care. Previous research has shown that context length and reasoning ability are closely intertwined. For an SLM, it’s extremely challenging to optimize both dimensions while keeping the parameter size small.

Today, we’re excited to announce the first version of this solution with the release of reader-lm-0.5b and reader-lm-1.5b, two SLMs specifically trained to generate clean markdown directly from noisy raw HTML. Both models are multilingual and support a context length of up to 256K tokens. Despite their compact size, these models achieve state-of-the-art performance on this task, outperforming larger LLM counterparts while being only 1/50th of their size.

Below are the two models' specifications:

| reader-lm-0.5b | reader-lm-1.5b | |

|---|---|---|

| # Parameters | 494M | 1.54B |

| Context length | 256K | 256K |

| Hidden Size | 896 | 1536 |

| # Layers | 24 | 28 |

| # Query Heads | 14 | 12 |

| # KV Heads | 2 | 2 |

| Head Size | 64 | 128 |

| Intermediate Size | 4864 | 8960 |

| Multilingual | Yes | Yes |

| HuggingFace Repo | Link | Link |

tagGet Started with Reader-LM

tagOn Google Colab

The easiest way to experience reader-lm is by running our Colab notebook, where we demonstrate how to use reader-lm-1.5b to convert the Hacker News website into markdown. The notebook is optimized to run smoothly on Google Colab’s free T4 GPU tier. You can also load reader-lm-0.5b or change the URL to any website and explore the output. Note that the input (i.e., the prompt) to the model is the raw HTML—no prefix instruction is required.

Please be aware that the free-tier T4 GPU comes with limitations that might prevent the use of advanced optimizations during model execution. Features such as bfloat16 and flash attention are not available on the T4, which could result in higher VRAM usage and slower performance for longer inputs. For production environments, we recommend using a higher-end GPU like the RTX 3090/4090 for significantly better performance.

tagIn Production: Available on Azure & AWS Soon

Reader-LM is available on Azure Marketplace and AWS SageMaker. If you need to use these models beyond those platforms or on-premises within your company, note that both models are licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0. For commercial usage inquiries, feel free to contact us.

tagBenchmark

To quantitatively evaluate the performance of Reader-LM, we compared it with several large language models, including: GPT-4o, Gemini-1.5-Flash, Gemini-1.5-Pro, LLaMA-3.1-70B, Qwen2-7B-Instruct.

The models were assessed using the following metrics:

- ROUGE-L (higher is better): This metric, widely used for summarization and question-answering tasks, measures the overlap between the predicted output and the reference at the n-gram level.

- Token Error Rate (TER, lower is better): This metric calculates the rate at which the generated markdown tokens do not appear in the original HTML content. We designed this metric to assess the model's hallucination rate, helping us identify cases where the model produces content that isn’t grounded in the HTML. Further improvements will be made based on case studies.

- Word Error Rate (WER, lower is better): Commonly used in OCR and ASR tasks, WER considers the word sequence and calculates errors such as insertions (ADD), substitutions (SUB), and deletions (DEL). This metric provides a detailed assessment of mismatches between the generated markdown and the expected output.

To leverage LLMs for this task, we used the following uniform instruction as the prefix prompt:

Your task is to convert the content of the provided HTML file into the corresponding markdown file. You need to convert the structure, elements, and attributes of the HTML into equivalent representations in markdown format, ensuring that no important information is lost. The output should strictly be in markdown format, without any additional explanations.The results can be found in the table below.

| ROUGE-L | WER | TER | |

|---|---|---|---|

| reader-lm-0.5b | 0.56 | 3.28 | 0.34 |

| reader-lm-1.5b | 0.72 | 1.87 | 0.19 |

| gpt-4o | 0.43 | 5.88 | 0.50 |

| gemini-1.5-flash | 0.40 | 21.70 | 0.55 |

| gemini-1.5-pro | 0.42 | 3.16 | 0.48 |

| llama-3.1-70b | 0.40 | 9.87 | 0.50 |

| Qwen2-7B-Instruct | 0.23 | 2.45 | 0.70 |

tagQualitative Study

We conducted a qualitative study by visually inspecting the output markdown. We selected 22 HTML sources including news articles, blog posts, landing pages, e-commerce pages, and forum posts in multiple languages: English, German, Japanese, and Chinese. We also included the Jina Reader API as a baseline, which relies on regex, heuristics, and predefined rules.

The evaluation focused on four key dimensions of the output, with each model rated on a scale from 1 (lowest) to 5 (highest):

- Header Extraction: Assessed how well each model identified and formatted the document’s h1,h2,..., h6 headers using correct markdown syntax.

- Main Content Extraction: Evaluated the models' ability to accurately convert body text, preserving paragraphs, formatting lists, and maintaining consistency in presentation.

- Rich Structure Preservation: Analyzed how effectively each model maintained the overall structure of the document, including headings, subheadings, bullet points, and ordered lists.

- Markdown Syntax Usage: Evaluated each model’s ability to correctly convert HTML elements such as

<a>(links),<strong>(bold text), and<em>(italics) into their appropriate markdown equivalents.

The results can be found below.

Reader-LM-1.5B consistently performs well across all dimensions, particularly excelling in structure preservation and markdown syntax usage. While it doesn't always outperform Jina Reader API, its performance is competitive with larger models like Gemini 1.5 Pro, making it a highly efficient alternative to larger LLMs. Reader-LM-0.5B, though smaller, still offers solid performance, particularly in structure preservation.

tagHow We Trained Reader-LM

tagData Preparation

We used the Jina Reader API to generate training pairs of raw HTML and their corresponding markdown. During the experiment, we found that SLMs are particularly sensitive to the quality of the training data. So we built a data pipeline that ensures only high-quality markdown entries are included in the training set.

Additionally, we added some synthetic HTML and their markdown counterparts, generated by GPT-4o. Compared to real-world HTML, synthetic data tends to be much shorter, with simpler and more predictable structures, and a significantly lower noise level.

Finally, we concatenated the HTML and markdown using a chat template. The final training data is formatted as follows:

<|im_start|>system

You are a helpful assistant.<|im_end|>

<|im_start|>user

{{RAW_HTML}}<|im_end|>

<|im_start|>assistant

{{MARKDOWN}}<|im_end|>

The full training data amounts to 2.5 billion tokens.

tagTwo-Stage Training

We experimented with various model sizes, starting from 65M and 135M, up to 3B parameters. The specifications for each model can be found in the table below.

| reader-lm-65m | reader-lm-135m | reader-lm-360m | reader-lm-0.5b | reader-lm-1.5b | reader-lm-1.7b | reader-lm-3b | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hidden Size | 512 | 576 | 960 | 896 | 1536 | 2048 | 3072 |

| # Layers | 8 | 30 | 32 | 24 | 28 | 24 | 32 |

| # Query Heads | 16 | 9 | 15 | 14 | 12 | 32 | 32 |

| # KV Heads | 8 | 3 | 5 | 2 | 2 | 32 | 32 |

| Head Size | 32 | 64 | 64 | 64 | 128 | 64 | 96 |

| Intermediate Size | 2048 | 1536 | 2560 | 4864 | 8960 | 8192 | 8192 |

| Attention Bias | False | False | False | True | True | False | False |

| Embedding Tying | False | True | True | True | True | True | False |

| Vocabulary Size | 32768 | 49152 | 49152 | 151646 | 151646 | 49152 | 32064 |

| Base Model | Lite-Oute-1-65M-Instruct | SmolLM-135M | SmolLM-360M-Instruct | Qwen2-0.5B-Instruct | Qwen2-1.5B-Instruct | SmolLM-1.7B | Phi-3-mini-128k-instruct |

The model training was conducted in two stages:

- Short-and-simple HTML: In this stage, the maximum sequence length (HTML + markdown) was set to 32K tokens, with a total of 1.5 billion training tokens.

- Long-and-hard HTML: the sequence length was extended to 128K tokens, with 1.2 billion training tokens. We implemented the zigzag-ring-attention mechanism from Zilin Zhu's "Ring Flash Attention" (2024) for this stage.

Since the training data included sequences of up to 128K tokens, we believe that the model can support up to 256K tokens without issue. However, handling 512K tokens may be challenging, as extending RoPE positional embeddings to four times the training sequence length could result in performance degradation.

For the 65M and 135M parameter models, we observed that they could achieve reasonable "copy" behavior, but only with short sequences (fewer than 1K tokens). As the input length increased, these models struggled to produce any reasonable output. Given that modern HTML source code can easily exceed 100K tokens, a 1K token limit is far from sufficient.

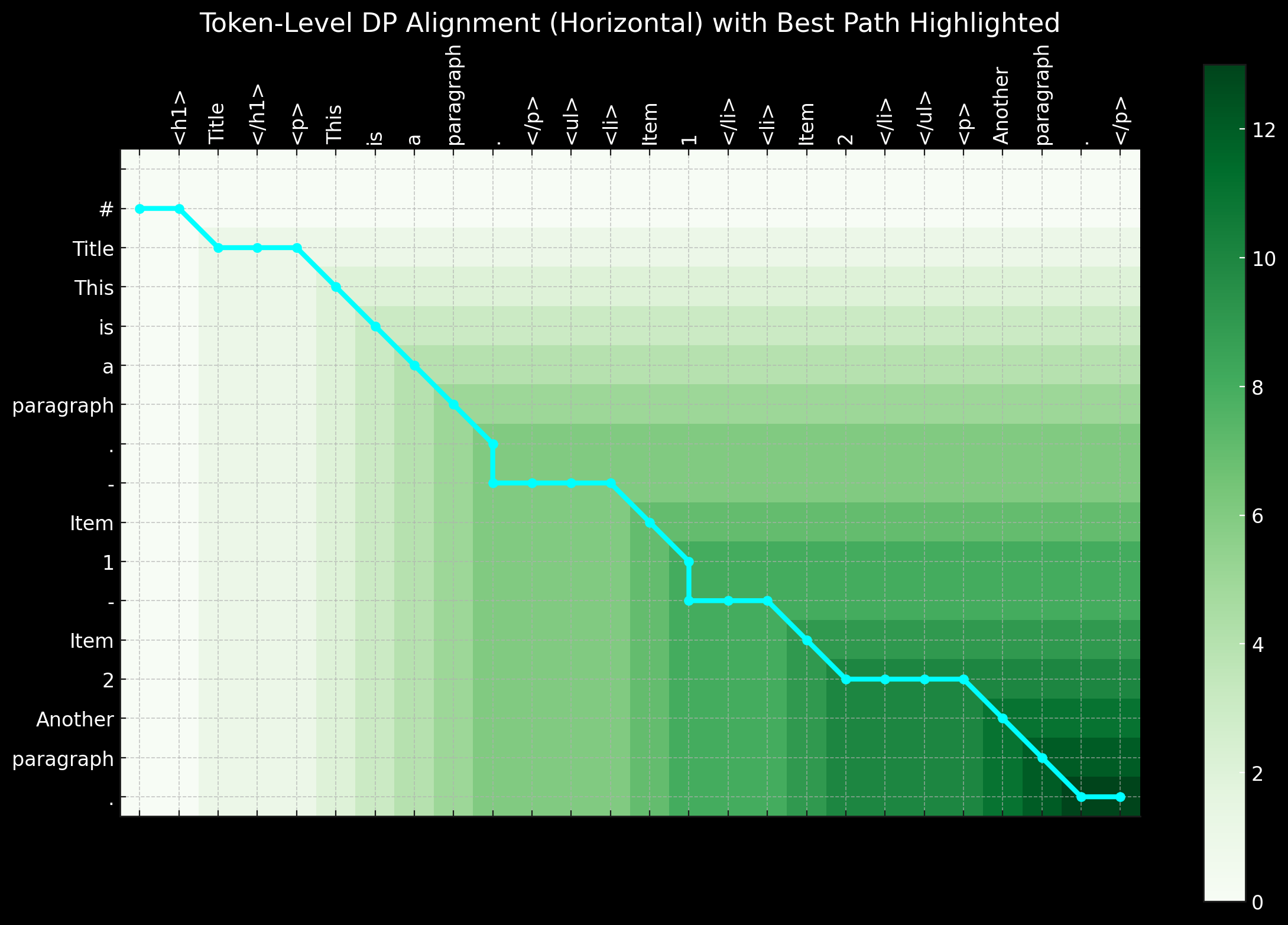

tagDegeneration and Dull Loops

One of the major challenges we encountered was degeneration, particularly in the form of repetition and looping. After generating some tokens, the model would begin to generate the same token repeatedly or get stuck in a loop, continuously repeating a short sequence of tokens until reaching the maximum allowed output length.

To address this issue:

- We applied contrastive search as a decoding method and incorporate contrastive loss during training. From our experiments, this method effectively reduced repetitive generation in practice.

- We implemented a simple repetition stop criterion within the transformer pipeline. This criterion automatically detects when the model begins to repeat tokens and stops decoding early to avoid dull loops. This idea was inspired by this discussion.

tagTraining Efficiency on Long Inputs

To mitigate the risk of out-of-memory (OOM) errors when handling long input, we implemented chunk-wise model forwarding. This approach encodes the long input with smaller chunks, reducing VRAM usage.

We improved the data packing implementation in our training framework, which is based on the Transformers Trainer. To optimize training efficiency, multiple short texts (e.g., 2K tokens) are concatenated into a single long sequence (e.g., 30K tokens), enabling padding-free training. However, in the original implementation, some short examples were split into two sub-texts and included in different long training sequences. In such cases, the second sub-text would lose its context (e.g., raw HTML content in our case), leading to corrupted training data. This forces the model to rely on its parameters rather than the input context, which we believe is a major source of hallucination.

In the end, we selected the 0.5B and 1.5B models for publication. The 0.5B model is the smallest one capable of achieving the desired "selective-copy" behavior on long-context inputs, while the 1.5B model is the smallest larger model that significantly improves performance without hitting diminishing returns in relation to parameter size.

tagAlternative Architecture: Encoder-Only Model

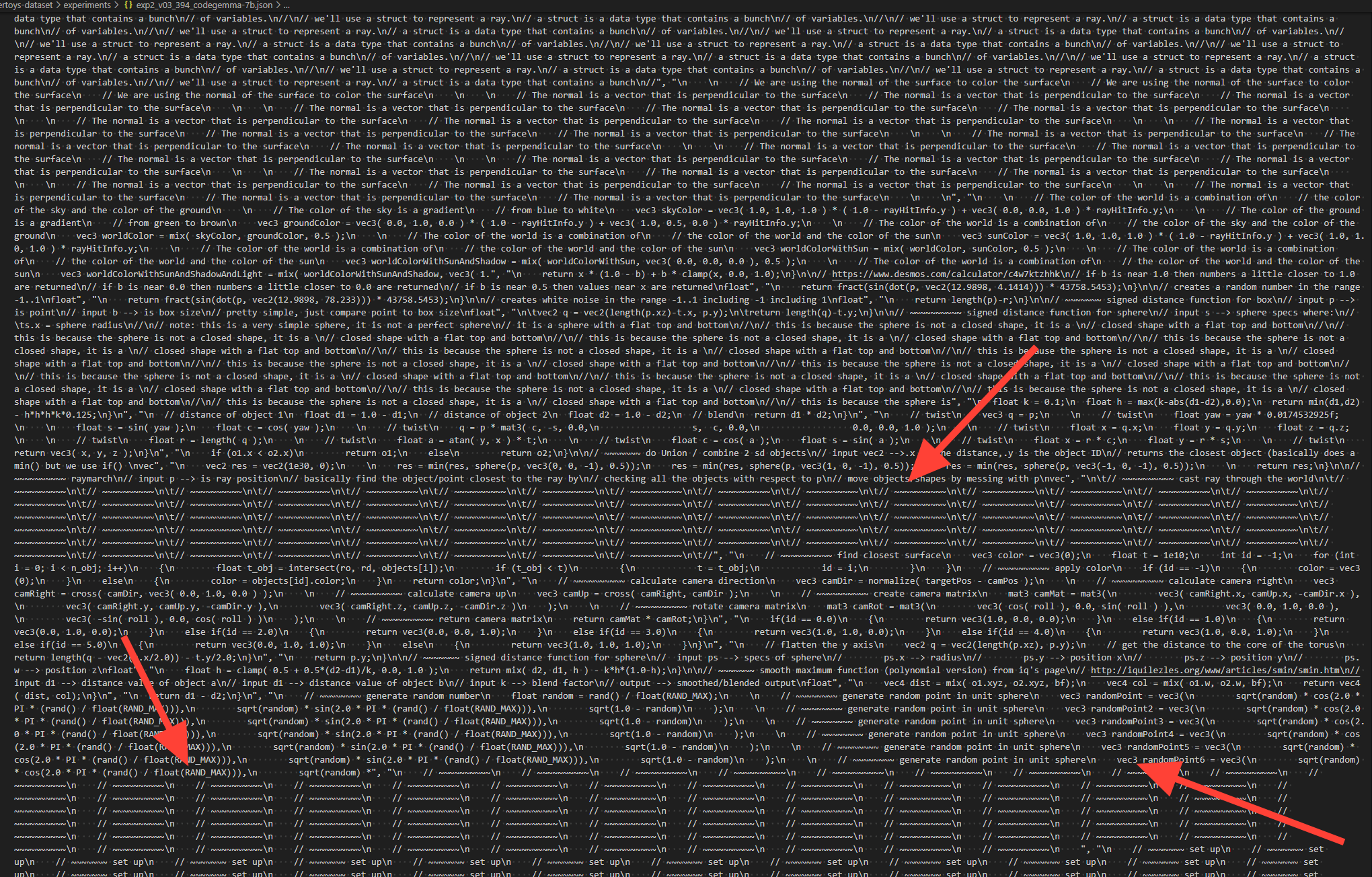

In the early day of this project, we also explored using an encoder-only architecture to tackle this task. As mentioned earlier, the HTML-to-Markdown conversion task appears to be primarily a "selective-copy" task. Given a training pair (raw HTML and markdown), we can label tokens that exist in both the input and output as 1, and the rest as 0. This converts the problem into a token classification task, similar to what is used in Named Entity Recognition (NER).

While this approach seemed logical, it presented significant challenges in practice. First, raw HTML from real-world sources is extremely noisy and long, making the 1 labels extremely sparse hence difficult for the model to learn. Second, encoding special markdown syntax in a 0-1 schema proved problematic, as symbols like ## title, *bold*, and | table | do not exist in the raw HTML input. Third, the output tokens do not always strictly follow the order of the input. Minor reordering often occurs, particularly with tables and links, making it difficult to represent such reordering behaviors in a simple 0-1 schema. Short-distance reordering could potentially be handled with dynamic programming or alignment-warping algorithms by introducing labels like -1, -2, +1, +2 to represent distance offsets, transforming the binary classification problem into a multi-class token classification task.

In summary, solving the problem with an encoder-only architecture and treating it as a token classification task has its charm, especially since the training sequences are much shorter compared to a decoder-only model, making it more VRAM-friendly. However, the major challenge lies in preparing good training data. When we realized that the time and effort spent preprocessing the data—using dynamic programming and heuristics to create perfect token-level labeling sequences—was overwhelming, we decided to discontinue this approach.

tagConclusion

Reader-LM is a novel small language model (SLM) designed for data extraction and cleaning on the open web. Inspired by Jina Reader, our goal was to create an end-to-end language model solution capable of converting raw, noisy HTML into clean markdown. At the same time, we focused on cost-efficiency, keeping the model size small to ensure Reader-LM remains practical and usable. It is also the first decoder-only long-context model trained at Jina AI.

Although the task may initially appear to be a simple "selective-copy" problem, converting and cleaning HTML to markdown is far from easy. Specifically, it requires the model to excel at position-aware, context-based reasoning, which demands a larger parameter size, particularly in the hidden layers. In comparison, learning markdown syntax is relatively straightforward.

During our experiments, we also found that training an SLM from scratch is particularly challenging. Starting with a pretrained model and continuing with task-specific training significantly improved training efficiency. There's still much room for improvement in terms of both efficiency and quality: expanding the context length, speeding up decoding, and adding support for instructions in the input, which would allow Reader-LM to extract specific parts of a webpage into markdown.